Decoding the wonderful localness of Barolo’s Nebbiolo

Quality of localness

Barolo’s localness lies in its small appellation and the connection of the local people with their land and vines. Its identity, rooted in tradition, reflects a historical commitment to producing complex wines that develop flavors of roses, tar, truffle, and spices over decades, demanding patience from both winemakers and wine lovers.

One day, I met a winemaker from the Barolo wine region

The winemaker struck up a conversation with me soon after I arrived at his winery. “I heard you traveled far and wide. How is it that you hardly made it to Barolo, the most famous DOCG in Italy?” I reassured him that I am not biased against Barolo; on the contrary, I adore its wines. “Consider this first,” I explained, “I am a restless, curious person, and unlike you, I do not have roots here. You still grasp localness, a connection to traditions of the land and local culture. Your localness needs patience, and not restlessness.”

If there is one consistent truth about Barolo, it is that it embodies patience. Open a bottle too soon, and it may taste brutal, high in tannins, acidity, and probably alcohol content too. But after you let it breathe or age in your cellar, the magic unfolds with time. Aging plays a critical role in shaping a Barolo wine. A Barolo must age for at least 38 months, with 18 months in oak. When you stretch your patience, it is always rewarding. Tasting a great Barolo is a kind of meditative act. The bold tannins and earthy complexity of an evolved Barolo make it an exceptional wine.

Barolo, the legendary “King of Wines”

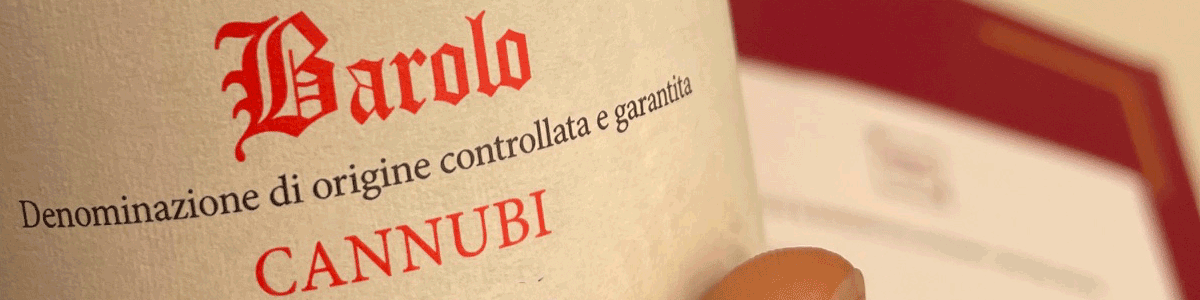

Barolo is a red wine made from the Nebbiolo grape. It is considered Italy’s noblest wine. True enough, as there are very few wines that can compare to the power of a legendary good Barolo. The high acidity, intense grippy tannins, structured full body, bone-dry palate of Barolo, and its intense aromas and flavours of dark cherry, plum, raspberry, roses, violet, lavender, white pepper, cinnamon, star anise, next to -in aged Barolo’s- clove, liquorice, truffle, tobacco, cedar and tar, earned Barolo wines many accolades. For one, the ability to convey a sense of place.

Nebbiolo draws its distinctive character directly from the soil

The rich soil in the Barolo wine region is composed of sediments, minerals, and alluvial moraines left behind by an ancient sea that flooded the wine region millions of years ago. The remaining sedimentary marine soils, with alternating layers of limestone, marl and sandstone, and varying percentages of clay and sand, make them ideal for the finicky Nebbiolo. Furthermore, the vines thrive on steep south or southwest-facing hillsides at altitudes between 200 and 450 meters.

Due to climate change, some producers are experimenting with less exposed vineyard sites and higher altitude plantings. The goal is to extend Nebbiolo’s long growth cycle and to slow the ripening. Nebbiolo buds early, towards the middle of April, and ripens later than most other varieties, around the middle of October.

Some facts

The Barolo DOCG appellation includes 11 villages, with the most recognised for their quality being Barolo, La Morra, Serralunga d’Alba, Castiglione Falletto, and Monforte d’Alba. Additionally, there are sub-areas known as MGAs (Menzioni Geografiche Aggiuntive). In total, Barolo comprises 181 single vineyards (or crus) classified as MGAs. This division of vineyards into sub-areas is a practice adapted from France, where a system of crus and grand crus identifies specific places of origin.

The earliest documented references to Nebbiolo date back to the 13th century, though the grape likely existed in the region long before it became the cornerstone of Italy’s winemaking heritage in the 18th century. Also named Spanna, Chiavennasca, and Prunent in other wine-growing regions, the oldest indigenous red grape vine of Piedmont derives its name from ‘nebbia’, the Italian word for mist or fog. The local autumn fog also plays a crucial role in the grape’s development, extending the growing season and allowing the thick-skinned grapes to achieve full phenolic ripeness.

Local legacy

As I walked through the vineyards next to the winery, I enjoyed the view of the river that divides the ancient hills of Barolo and La Morra from those of Castiglione Falletto and Serralunga d’Alba. It was there that my host pointed out where soils from different geological eras converge. I was told that this unique site enhances the classic characteristics of Barolo: the aromatic nose, flavourful fruit, and tannins, all elements that give a wine an elegant sapidity, distinct from many neighbouring sites.

My host remarked, “part of the beauty of wine is that tasting takes you beyond flavour into feeling. It engages your senses.” Looking down on the hill, I regret not having explored Barolo more. Time seemed to slow down in this quiet, tree-bordered place. Yes, these vines have deep roots; their localness is not lost on me. I have listened to the land, but perhaps my recent wisdom is that I don’t know it. What is so wonderful that I can taste its wines and come to Barolo again, and again.