Champagne’s forgotten grapes reveal a potential for acidity and freshness

Champagne

As a result of climate change Champagne’s grapes are being very ripe, while the acidity has decreased in grape must. To preserve acidity, a winemaker can use no less than 7 grapes in a blend, including the 4 forgotten ones.

Knowing your way in the world of champagnes is not an easy task. There is always the question of overflowing abundance. Champagne brands you don’t know, big brand versus grower champagnes, different blends with various dosages, contrasting years or vintages. Yet, another question pops up too. What kind of influence does climate change have on cool climate Champagne making? Will producers add more of Champagne’s forgotten grapes to preserve Champagne’s crisp, fresh style?

Champagne’s producers and grape growers are struggling to adapt to climate change

Global warming is a fact in Champagne. Comité Champagne (CIVC) states that temperatures have increased close to 1.2°C in 30 years. Although 1.2°C doesn’t sound like much, it makes a huge difference in the growing cycle of Champagne’s grapes. The rise in temperature can have a potentially devastating effect on Champagne’s viticultural practices. And it does not stop there. Climate change can affect Champagne’s wine styles too, and possibly its quality.

The prediction of future weather is a key ingredient in good vineyard risk management. Lately, however, the lack of weather predictability is becoming a problem. Hotter summers, extended droughts, unexpected heat waves, and sudden spring frosts, it all adds up, but changes are increasingly difficult to predict. Climate change and global warming are forcing winemakers to adapt year by year and to find new innovative ways for work in the cellar, during harvest and grape growing.

Acidity is essential to Champagne’s taste

What now, we wondered, if Champagne becomes too hot, and the weather too unpredictable? Can the growers at that point still work with the classic three grape varieties Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay? An increase in average temperatures often results in higher levels of ripeness in grapes, in more sugars, in wines with a riper flavor profile, but also in wines that lack a key ingredient: acidity or freshness. Acidity allows the wines to age, gives the wines freshness, and that indescribable “oomph”. According to the CIVC acidity in Champagne has been reduced by 1.3 g/l on average in the last 30 years. And still, the acidity levels are expected to fall even more in the future.

Champagne is trying to maintain its style

Champagne’s technique of blending different varieties, grapes from various vineyards, and vintages to create a blend -of freshly fermented and reserve wines from older vintages- always worked, but not anymore. To create depth, complexity, and richness it is paramount to have enough acidity or freshness in the blend. A “classic” Champagne is crisp, fruity when young, with zingy acidity, and mineral, slightly salty, brioche flavours. Champagne winemakers now have to resolve to winemaking techniques such as blocking malo-lactic fermentation* or reducing the dosage* to keep the acidity in the wine. Others experiment with biodynamic viticulture, gentler forms of pruning, the results of DNA analysis, yeasts, or grapes.

Champagne’s forgotten grapes or the legacy grapes

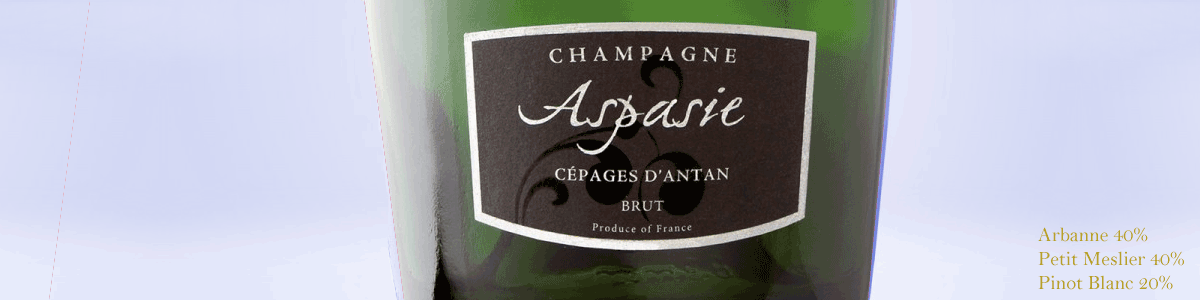

What many people often not know is that no fewer than seven grapes are allowed in champagne wines. There are the big three, Pinot Noir (38%), Pinot Meunier (31%), and Chardonnay (30%), amount to 99% of the planted vines. While the other four approved, more rare, varietals, Petit Meslier, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, and Petit Arban(n)e, account for less than 1% of the vines.

Not surprising that growers en producers revive interest in Champagne’s forgotten grapes also called legacy grapes. Particularly Petit Arbane and Petit Meslier have the grower’s interest, in view of their high levels of natural acidity. Meslier and Arbane ripen slowly and bring freshness to champagnes due to their low PH values, sometimes even below 3.0.

Petit Meslier first appeared in the North of France, probably in the Vallee de la Marne

Petit Meslier is a white variety, a natural cross between Gouais Blanc x Savagnin. Meslier grows very slow and has small, compact berries. Once Meslier was widely planted in Champagne due to its ability to retain acidity, even in warmer vintages. As a still wine it is crisp, showing a certain greenness with lots of apple and herbaceous notes. Champagne house Duval-Leroy makes Precious Parcel Petit Meslier Vintage Champagne only from Petit Meslier. Unfortunately, they only produce 988 bottles.

The history of Pinot Blanc presumably starts in Burgundy and Champagne

Pinot Blanc is grown in tiny amounts in the Champagne region. In the past often mistaken for Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc was first accepted as a separate grape variety in 1872 at the Lyon viticultural exhibition. It now grows more extensively in the Alsace. Pinot Blanc, named Blanc Vrai in Champagne, belongs to the Pinot family and is early budding and early ripening. More gentle pruning than usual is needed, as it has big grapes and is susceptible to botrytis. Tassin Excellence is a blend from old vines, notably Pinot Blanc, a grape they call rare and delicate. In the southern Aube region, winery Pierre Gerbais makes a 100% Pinot Blanc Champagne -L’Originale Extra Brut Pinot Blanc- from vines planted in 1904. Likewise, Champagne Pierre Trichet released its “Cuvée 1333″ made from 100% Pinot Blanc.

Petit Arbane was historically planted in the Aube region of Champagne

Petite Arbane is a white grape variety, originally planted in the Aube region of Champagne. Now very rare, Arbane is mainly used in blends of 6 or 7 cépages – often a field blend of 6 or 7 grape varieties-, but there is a 100% Arbane Champagne on the market called Vieilles-Vignes, made by Champagne Moutard-Diligent. Champagne Gruet makes Cuvee Arbane too. And Olivier Horiot a 100% Arbane Champagne Biologique.

Pinot Gris -also called Fromenteau in Champagne- is most likely to be native to Burgundy

Pinot Gris was widely grown in the Champagne region back in the 18th century. Plantings in Champagne dwindled as the grape was found to be unreliable and low yielding. The bunches are prone to mildew and botrytis. Pinot Gris adds fruitiness and moderate acidity to a blend. Aside, subtle aromas of white flowers, melons, pears, apples, and almonds plus honey when more mature. It ripens very early and the grapes range from a grey-blue to rose brown in colour. Pinot Gris in Champagne is mainly used in blends, such as the one of Aubrey Champagne’s cuvée – Le Nombre d’Or. Le Nombre d’Or brings together the historic grape varieties of Champagne: Fromenteau or Pinot Gris, Petit Meslier, Arbane, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay.

Everything comes down to balance, to what tastes best

When we’ll try to answer the question ‘does climate change threatens to change Champagne’s unique taste?’ it is like finding an answer to the question of how champagne tasted 30, 100, or 200 years ago. In the past, the climate was colder in Champagne and the grapes were usually picked before reaching full maturity. The wines were acidic and low in alcohol, adding carbon dioxide significantly improved the wines. Grapes picked a little green, rather than ripe, make better sparkling wines. Common knowledge, already the. Only in the 19th-century one started to systematically use sugar to boost the levels of carbon dioxide in sparkling wines.

Every era has it’s own dosage preferences

In the past, different export markets preferred different levels of sweetness. In general, past Champagnes contained a considerably higher dosage than today. In the 19th century, the English favoured the driest style of all, a mere 22-66 grams per liter of sugar. Demand in Germany, the United States, and Scandinavian countries prefered even sweeter styles, up to 200 grams per liter. One spoke in those times about the goût Anglais, goût Américain and goût Russe. Russia, however, had a sweet tooth, they fancied champagnes with up to 330 grams per liter of sugar. Especially in today’s world, this seems overly sweet.

Champagnes that reflect terroir

Nowadays, especially among the grower champagne producers, there is a tendency towards a reassessment of the dosage. They prefer to create champagnes that reflect their terroir. They often feel that the dosage gets in the way of terroir expression. For them experimenting with low-dosage and zero-dosage seems a logical progression to balance out the ripeness and declined acidity. Bottom line: everything comes down to balance, to what tastes best. And for some, to the debatable matter of typicity, to instantly recognise an area’s or grape’s unique taste. However difficult that might be.

Can you instantly recognise Champagne’s unique taste also in champagnes made of the forgotten grapes?

Of the champagnes I tasted made of the four legacy grapes, all had more or less the same characteristics as the so-called “classic” champagnes, although there were nuanced style differences. Producers say that these differences are generated by the characteristics of the grapes, terroir influences, composition of the blend, dosage differences, and the ageing time. Still, even with climate changes, you can easily recognise the quality of a typical Champagne. To keep it this way, Champagne needs to retain the acidity so necessary for the fresh, crisp taste and ageing process -on lees- in wines and reserve wines.

Will climate change add a new dimension to Champagne? Let’s find out. The next time you open a champagne bottle, take a look at the grapes mentioned on the back label. Did the producer add one or more of Champagne’s forgotten grapes? In the end, nobody needs an excuse to check their tasting skills. Champagne is Champagne. And we all love a good bottle of Champagne, don’t we?

Notes:

*1 malo-lactic fermentation converts aggressive apple or malic acid to a softer lactic acid.

*2 dosage – a small quantity of wine and (cane) sugar added back to each bottle of champagne after disgorging to balance the naturally high acidity of the wine, also known as liqueur de expedition.

*3 goût – taste or taste preference

Terroir is a plot or area with certain physical, topographic, and climatic properties. These factors create a distinct wine with a unique character and unique organoleptic properties.